Çe sera un long hiver et pour la plupart d’entre vous, une saison à la recherche et à la planification de voyages à venir, de journées à rêver à la navigation de plaisance et aussi à la lecture d’articles ou de livres sur la navigation de plaisance. Présenter ici, un chapitre de «Contes de bord” onze récits de mer réunis par Édouard Corbière et publiés en 1834. Chaque semaine Boathouse présentera un chapitre ou deux de cette œuvre du domaine public et nous espérons que cela facilitera le passage de l’hiver pour nos lecteurs. Si vous êtiez impatients et ne pouviez pas attendre la suite de ce récit à chaque semaine, vous pourriez lire le livre en entier sur gutenburg.org.

Boathouse

———————————————

UN CONTRE-AMIRAL EN BONNE FORTUNE.

Un général de mer se plaisait à tyranniser les officiers de la division qu’il commandait, à peu près comme autrefois certain empereur romain s’amusait, pour passer le temps, à tuer des mouches. En retour de ses mauvais traitemens, tous ses officiers l’envoyaient au diable; mais leurs malédictions ne réussissaient qu’à réjouir le vieil amiral, qui se montrait fier surtout de la haine universelle qu’il inspirait; et les arrêts forcés ne réjouissaient nullement les jeunes officiers.

Lorsque l’amiral riait en montant à bord, on pouvait en conclure qu’il venait de jouer quelque bon tour à l’un des élégans de la division. Rien ne l’égayait autant que de pouvoir dire à son capitaine de pavillon: «Monsieur le commandant, vous ordonnerez les arrêts forcés pour quinze jours à M. un tel, qui s’est permis d’aller faire la belle jambe à terre malgré mes ordres.» Il se serait volontiers pâmé d’aise, lorsqu’après avoir rencontré dans une rue un officier déguisé en matelot, il lâchait aux trousses du pauvre fugitif deux ou trois de ses adjudans. Il appelait cela faire la chasse aux lapereaux. Cet homme aurait fait le meilleur chef de police que l’on pût posséder dans une capitale. Le sort, en se trompant, n’en avait fait qu’un contre-amiral.

Tous les officiers lui rendaient depuis long-temps haine pour vexations, et cette haine était devenue telle, qu’on pouvait dire qu’elle avait fini par dégénérer en esprit de corps. Il était d’usage de détester l’amiral, à peu près comme il est ordinaire, dans le service, de respecter ses chefs. C’était presque un article de l’ordonnance.

Mille fois on se serait vengé de ce damné d’homme, si les règles d’une discipline d’airain avaient pu se prêter aux voeux que les subalternes formaient contre leur injuste et inflexible chef. Mais, comme il le disait lui-même, il était le pot de fer, et il ne redoutait pas les cruches qui auraient osé l’aborder.

Les cruches enrageaient donc de n’avoir pu ébrécher le pot de fer que par quelques piquantes plaisanteries et quelques bonnes épigrammes auxquelles leur puissant adversaire avait toujours riposté par les arrêts forcés ou de mauvaises notes envoyées au ministre.

Un jeune enseigne de vaisseau, malgré les difficultés et les dangers de l’entreprise, résolut cependant de venger tous ses camarades de la longue humiliation sous laquelle la main de l’amiral avait courbé leurs fronts craintifs. «Je veux, leur dit-il, pour peu que le ciel seconde mes projets, couvrir de honte celui qui nous a jusqu’ici accablés de vexations. Faites des voeux pour moi, et laissez-moi faire.»

La division se trouvait mouillée depuis quelques jours dans un port étranger. Le Léonidas qui aspire à arrêter le torrent des mauvais traitemens de l’amiral, ne choisit pas pour compagnons trois cents Spartiates, mais il prend avec lui les deux plus jolis petits aspirans qu’il peut trouver, et il marche aux Thermopyles. Mais quelles sont les Thermopyles de notre officier? une maison de joie qu’il loue pour quelques heures à d’aimables filles dans une des rues les plus fréquentées de la Havane.

Les deux petits aspirans, dont les traits sont doux et malins, et dont la taille est encore petite et svelte, se laissent habiller en jeunes personnes. Leur teint, déjà un peu bruni par l’air brûlant de la mer, reprend toute sa fraîcheur native sous une légère couche de blanc de céruse. Leurs pieds adolescens, long-temps comprimés par des bottes épaisses, recouvrent une élégante flexibilité dans de fins souliers de prunelle. Leurs hanches, comprimées sous la ceinture d’un lourd poignard, se dessinent voluptueusement sous un large ruban rose. Nos deux petits chérubins de bord deviennent enfin, avec un peu d’art et de patience, de jolies petites filles agaçantes, faites pour tromper l’oeil enflammé de plus d’un amateur. Au bout de quelques heures d’exercice à la fenêtre du logis où l’on vient de les installer, elles auraient pu prendre dans leurs filets les passans les moins disposés à se laisser séduire par les agaceries de ce sexe dont l’empire s’étend si facilement de la croisée à la rue.

L’amiral, le soir même du jour où nos masculines Laïs étaient entrées en fonctions, s’était rendu au spectacle accompagné d’un de ses aides-de-camp. A onze heures il s’en revenait à bord, précédé par deux matelots qui, sur ses pas, avaient soin de projeter la vive clarté de deux énormes fanaux. En passant par une des rues qu’il lui fallait parcourir pour se rendre vers le warf où l’attendait son canot, il fait remarquer à l’aide-de-camp marchant respectueusement à ses côtés, deux fenêtres d’où sortent des voix qu’il croit reconnaître pour des voix de femmes, et de femmes françaises même!

«Quelle drôle de chose, à la Havane, à cette heure, monsieur mon aide-de-camp! Qu’en dites-vous?

—Mon général, je dis que ce n’est pas plus drôle que partout ailleurs. Il y a dans tous les lieux du monde connu, des Françaises qui font ce métier-là.»

—Quel métier entendez-vous donc?

—Mais, mon général, le métier que font probablement ces deux dames.

—Vous avez raison, elles sont deux, et elles me paraissent même être assez gentilles. Ecoutez! elles parlent…. Il me semble même qu’elles parlent de nous.»

Une de ces dames, en effet, en voyant passer le petit cortège, s’était écriée avec le doux accent de la curiosité et de l’intérêt:

«Ah! c’est le général français nouvellement arrivé!

—Voyez-vous, monsieur mon aide-de-camp, reprend l’amiral en recueillant ces paroles tendrement provocatrices, voyez-vous que ce sont des Françaises!… Mesdames, j’ai bien l’honneur de vous saluer….»

Les dames répondent gracieusement à ce salut…. La porte de la rue, près de laquelle les deux passans se sont arrêtés, s’entr’ouvre au même instant. Les matelots qui portaient les fanaux destinés à éclairer le général, se sont arrêtés aussi…. Mais le général leur ordonne de continuer leur route sans lui, en leur recommandant d’avertir leur patron qu’il ira bientôt rejoindre son canot.

Resté seul avec son aide-de-camp, et délivré de la présence importune de ses deux matelots, il reprend plus librement la conversation avec son interlocateur.

«Si, pour la singularité du fait, nous montions, monsieur l’aide-de-camp?

—Chez ces dames?

—Mais où voulez-vous que nous montions, si ce n’est chez elles?

—Y pensez-vous sérieusement, mon général?

—A quoi voulez-vous que je pense, si ce n’est à ce que je vous propose?

—Mais que dira-t-on si l’on vient à savoir que….

—On dira que j’ai fait le galant et vous un peu le cafard, peut-être! Quel mal y aura-t-il à cela? Partout on veut me faire passer pour une espèce de Hun farouche, insensible à toutes les douces séductions du sexe…. J’ai envie de perdre ce soir une aussi fâcheuse réputation…. Allons, soyez aimable une fois en votre vie. Vous aussi vous n’avez pas plus que moi de temps à perdre pour réparer vos longues années d’endurcissement et de rébellion contre le pouvoir des belles. Entrons. Je vais vous donner l’exemple en ma qualité de chef.

—Mais une seule observation, mon général, elle ne sera pas longue.

—Cela ne l’empêchera pas d’être peut-être fort déplacée, votre observation, et encore assez ennuyeuse probablement.

—En entrant dans cette maison, vous ne risquez rien, vous….

—Il me semble cependant que je risque tout autant que vous au moins?

—Ce n’est pas cela que je veux dire. Je veux dire que le rôle que je jouerai en vous suivant pourra, en ma qualité de subalterne, paraître un peu trop complaisant, et que si l’on vient à apprendre plus tard….

—Ah! oui, vous craignez en votre qualité de subalterne, n’est-ce pas, que l’on dise que…. Quel enfantillage! Est-ce que dans ces sortes d’aventures tous les rangs ne sont pas égaux! Vous voyez bien même que dans la situation où nous nous trouvons, c’est moi qui fais tous les frais de la négociation; et, le diable m’emporte, je crois que si j’avais une chandelle à la main, je serais obligé de vous la tenir pour vous engager à monter l’escalier, tant ce soir vous paraissez tenir à faire la prude. Allons donc, montons, et que cela finisse!

—Puisqu’il le faut et que vous le voulez décidément, montons, mon général. Mais en grand uniforme….

—Pourquoi pas? personne ne nous voit, et la nuit sauve le scandale.»

Pendant tout ce colloque, nos deux syrènes avaient mis en usage leurs plus agaçantes minauderies pour séduire notre vieux navigateur et son scrupuleux compagnon. Leurs enchantemens n’avaient, hélas! que trop triomphé de la faiblesse de cet autre Ulysse.

En entrant dans l’appartement de nos piquantes Françaises, le général fut agréablement surpris de la richesse qui régnait dans le simple ameublement du lieu.

«Je reconnais bien là, s’écria-t-il pour dire quelque chose, le goût et l’élégance de mes compatriotes.»

Les deux beautés reçurent ce compliment d’introduction en faisant une révérence assez gauche et en baissant modestement la tête pour ne pas éclater de rire.

«Mais par quel hasard, ou plutôt par quel destin favorable pour nous, vous trouvez-vous ici, mes belles dames, au milieu de messieurs les Espagnols?

—Des événemens qu’il serait trop long de vous raconter, nous ont conduits … c’est-à-dire nous ont conduites dans ce pays, et ensuite des malheurs nous y ont retenues….

—Vous me trouverez peut-être un peu indiscret, mais l’intérêt que je porte à toutes les jolies femmes de ma patrie excusera la singularité de ma question…. Mesdames, êtes-vous demoiselles ou mariées?

—Nous étions mariées, monsieur le général.

—Et messieurs vos maris?

—Ne sont plus…. Des chagrins et l’inclémence du climat….

—Ah! j’entends, j’entends … la fièvre jaune, n’est-ce pas?… Ah! ce maudit climat…. (Voyez-vous, monsieur l’aide-de-camp, que ce sont des femmes distinguées: l’inclémence du climat….) Mais, mesdames, il paraît que l’air de la Havane, tout redoutable qu’il est, s’il vous a ravi les objets de votre tendresse, a respecté au moins les roses de votre teint; car il serait difficile, avec cette fraîcheur, que l’on ne vous reconnût pas pour françaises.

—Monsieur le général, vous êtes trop bon!

—Non, je ne suis que sincère. Et à cette taille élégante et à cette tournure qu’on n’a qu’en France, on se sent vraiment fier d’être de son pays…. Et qu’en dites-vous, monsieur l’aide-de-camp?

—Je dis, mon général, que vous avez raison, et que les Françaises sont des femmes charmantes.

—Mais il me semble que ces dames, sans doute pour charmer l’ennui du veuvage, ont adopté les moeurs du pays où elles se trouvent exilées; car voilà une guitare, si je ne me trompe.

—C’est une mandoline, général. Oui, quelquefois ma compagne a la bonté de m’accompagner sur cet instrument, confident discret de nos peines!… Ah!

—Ah! vous en pincez, madame: je vous y prends, et je tiens note de l’aveu.

—Mais j’en pince un peu, monsieur le général, je ne m’en défends pas.

LE GÉNÉRAL A SON AIDE-DE-CAMP.—Hum, mon ami, c’est significatif cela, j’espère. Vous ne vous étiez pas trompé. (A ces dames). Vous allez nous chanter une petite chanson, une chanson de France.

UNE DES DAMES.—Je chante si mal!

L’AUTRE DAME.—J’en pince si peu!

—Modestie que tout cela, modestie! Vous allez chanter et en pincer, aimables friponnes. Nous écoutons.

—Mais avant de nous soumettre à l’épreuve que vous voulez nous faire subir ou subir vous-mêmes, messieurs, voudriez-vous vous rafraîchir?… Domingo! Domingo! apportez des confitures et du Sangari à monsieur le général.

—Si Señora,» répond un gros nègre.

Le général dépose sur un canapé son épée et son chapeau. L’aide-de-camp en fait autant. Voilà Mars désarmé par l’Amour.

Une des syrènes chante la plaintive romance. Son amie l’accompagne sur sa mandoline, en faisant rouler sur le général des yeux qu’elle s’efforce de rendre caressans et fripons. Le général est transporté d’aise et d’ivresse.

«Comment trouvez-vous cette voix? demande-t-il à son compagnon.

—Un peu forte, mais assez bien timbrée.

—Et la pinceuse de guitare ou de mandoline?

—Elle me paraît avoir les mains assez fortes et le pied un peu épais.

—Vous ne savez ce que vous dites!

—Je sais bien au moins, mon général, ce que je vois.

—Elles sont charmantes, parfaites en tout; c’est moi qui vous le dis, et je m’y connais.»

Le chant a cessé: les tendres émotions commencent; les félicitations et les complimens vont leur train. Les oeillades se croisent et s’enflamment en se croisant. La pinceuse de mandoline se lève pour suspendre son instrument sonore à l’une des cloisons de l’appartement. En se levant avec grâce, elle sent deux mains un peu roides se presser sur la taille qu’elle s’efforce de dessiner d’une manière avantageuse. Ce sont les mains frémissantes du général qui se sont égarées sur ses hanches. La prude veut se fâcher et repousser avec dignité cet attouchement un peu trop leste. Le général devient plus pressant: il avance toujours: la belle recule jusque vers le canapé, et là, pour faire, en présence d’une attaque trop vive, une retraite digne d’elle, elle s’empare de l’épée et du chapeau du héros, et la coquette disparaît, avec la légèreté d’une sylphide, dans une chambre voisine, en poussant de grands éclats de rire. L’amoureux amiral veut la suivre, sûr qu’il paraît être de son triomphe: mais sa conquête lui échappe encore en grimpant les marches d’un escalier obscur qui paraît conduire au second étage.

Attiré par ce bruit, un gros gaillard à la figure basanée, au menton barbu, et à l’air rébarbatif, entre et arrête ses deux gros yeux noirs et irrités, sur le général…. Cet homme semble être un de ces bravos de la Havane, qui vendent au premier venu, une ou deux gourdes, chaque coup de stylet. Il baragouine quelques mots d’espagnol qui signifient qu’il est le chef de l’établissement. Le général à cette vue veut saisir son épée: elle a disparu! L’aide-de-camp cherche aussi la sienne: elle a disparu de même. La violence triomphera.

«Dans quel guêpier nous sommes-nous jetés là, mon cher ami!

—Ce n’est pas un guêpier, général…. Je vous l’avais bien dit.

—Emparons-nous, si vous m’en croyez, de ces barreaux de chaise, et forçons le passage.

—Forçons le passage, puisque nous ne pouvons faire autrement, et tapons, puisque vous le voulez, mon général. Mais c’est là une bien cruelle extrémité.»

Deux autres bravos espagnols s’avancent: les deux dames se tiennent derrière cette force imposante, arrivant tout exprès pour les protéger: elles rient toujours aux éclats en montrant aux deux officiers désarmés les deux épées et les chapeaux dont elles se sont si perfidement emparées.

«Tas de coquines, me rendrez-vous mon épée! s’écrie en les menaçant le général exaspéré.

—Dinero, dinero! s’écrient les bravos.

—Cela veut dire: Payez, payez, messieurs, et l’on vous rendra vos armes, répètent les dulcinées.

—Nos armes! Tiens, dit le général en jetant aux pieds des malheureuses qui le narguent, une bourse d’or pour rançon; tiens, ramasse cet argent, et rends-nous les armes et les chapeaux que tu nous as volés.»

Les bravos se nantissent d’abord de la bourse. Ils descendent ensuite l’escalier: les deux donzelles les suivent sans rien restituer. Le général et son aide-de-camp veulent aussi gagner la rue. Mais les portes par lesquelles le cortège s’est esquivé se referment sur eux, et pour comble de rage, les victimes entendent dans la rue leurs bourreaux crier: A la guarda! à la guarda! Nul doute, la garde va venir.

Elle arriva en effet. Le sergent de la patrouille, en ouvrant violemment la porte de la maison où le scandale avait lieu, reconnaît dans les deux officiers désarmés et décoiffés, le général de la division française et l’un de ses aides-de-camp. On s’explique du mieux qu’on peut, en espagnol et en français. Le sergent croit apprendre quelque chose de très-nouveau au général, en lui annonçant qu’il se trouve dans une maison suspecte. Le général demande pour toute grâce au chef de la force armée la faveur d’être reconduit à l’embarcation de son vaisseau, qui l’attendait au warf. Mais dans quel état il parut aux yeux de ses canotiers! sans épée et sans chapeau! Les canotiers ne savent que penser de cette circonstance singulière. Ils se contentèrent de nager jusqu’au vaisseau, et là encore, en montant à bord, le général et son piteux camarade en bonnes fortunes, eurent la honte de passer, en faisant de grands saluts, devant l’officier de garde qui les recevait à la lueur des fanaux allumés pour éclairer leur marche. Le lendemain de cette aventure, les flâneurs de la Havane aperçurent, suspendus à un poteau de réverbère, deux chapeaux et deux épées surmontés de cette inscription: «A VENDRE POUR CAUSE DE DÉPART PRÉCIPITÉ.»

Et puis on entendit dire dans toute l’île que le général commandant la division française avait fait hommage de sa bourse, à la caisse des indigens du pays.

Mais ce qu’il y eut de plus étrange dans tout cela, c’est le bruit qui courut avec la rapidité de l’éclair dans toute la division. Les officiers se disaient que les deux coquines qui avaient si adroitement décoiffé et désarmé leur général, n’étaient autre chose que deux petits aspirans travestis, et qu’en cherchant bien parmi les enseignes de vaisseau, on aurait pu reconnaître peut-être les deux ou trois bravos qui avec leur longue barbe factice et leur teint d’emprunt, avaient si galamment assisté les deux belles. Un des légers échos de ce bruit scandaleux alla frapper assez désagréablement l’oreille inquiète du général. Il devina bientôt toute la vérité, et il s’emporta d’abord comme un lion pris dans un piége. Il appela son aide-de-camp. «Vous savez, monsieur, le tour infâme qu’on nous a joué.

—Général, je commence depuis ce matin à m’en douter un peu.

—Je puis ordonner une enquête terrible, et faire fusiller les scélérats qui ont attenté à mon honneur. Commencez-vous à vous douter un peu aussi de toute l’étendue de mon autorité?

—Jamais, mon général, je n’en ai douté. Vous pouvez, il est vrai, ordonner une enquête: une enquête est même une chose excellente; mais n’y a-t-il pas eu, à votre avis, mon général, assez de scandale comme cela?

—Et comment vous, chef d’état-major, vous mon plus fidèle limier en quelque sorte, qui devriez deviner chaque officier de la division rien qu’à l’allure et au pas, n’avez-vous pas reconnu, flairé, dépisté deux polissons d’aspirans dans ces deux coquines de la nuit d’avant-hier?

—Vous les trouviez si aimables et si gentilles, mon général, que le moindre soupçon m’aurait paru inconvenant.

—Moi, je les trouvais gentilles! allons donc! vous ne voyiez pas que je me moquais d’elles? C’est vous peut-être que je devrais faire casser comme du verre, pour ne vous être pas douté de ce que vous deviez savoir mieux que tout autre.

—Moi, mon général, mais il me semble que vous feriez encore mieux d’ordonner une enquête, comme vous en avez eu d’adord l’idée, si décidément vous tenez à faire quelque chose de décisif.

—Ah! je suis bien malheureux! et ne pouvoir pas me venger sans augmenter le scandale! et dévorer ma honte, si je ne me venge pas!… Monsieur l’aide-de-camp!

—Plaît-il, mon général?

—Allez dire à l’officier chargé des signaux, que je lui ordonne d’annoncer à MM. les commandans de la division, que je mets tous les officiers aux arrêts forcés jusqu’à nouvel ordre!…

—De suite, mon général, j’y cours!

—Attendez donc un peu; que diable! aujourd’hui vous êtes bien prompt!

—Qu’y a-t-il encore pour votre service, mon général?

—Il y a pour mon service que, quand vous aurez exécuté l’ordre que je viens de vous donner, vous garderez les arrêts forcés vous-même, pour vous apprendre un autre fois à mieux faire votre devoir.

—Oui … oui … mon … mon général!… J’y vais!

—————————————-

A note from Boathouse:

It’s going to be a long winter and winter for most is a season to research and plan upcoming trips, day dream about boating and also read about boating. Presented here a chapter of ‘The Riddle of the sands’ an excellent pre WWI sailing adventure. Every week Boathouse will present a chapter or two of this public domain work and hopefully this will ease the passage of winter for our readers. If you are inpatient and can’t wait for each weeks installment you can read the entire book at gutenburg.org If you would rather listen to the book here is a link to an audio version: Chapter 7 & Chapter 8

If you would like to be notified when posts are added to this blog please send an email to blogadmin@boathouse.ca with the words ‘Subscribe to blog’ as the subject.

Have fun! Post a comment, let us know what you think.

Boathouse

————————————–

VII.

The Missing Page

I WOKE (on 1st October) with that dispiriting sensation that a hitch has occurred in a settled plan. It was explained when I went on deck, and I found the Dulcibella wrapped in a fog, silent, clammy, nothing visible from her decks but the ghostly hull of a galliot at anchor near us. She must have brought up there in the night, for there had been nothing so close the evening before; and I remembered that my sleep had been broken once by sounds of rumbling chain and gruff voices.

‘This looks pretty hopeless for to-day,’ I said, with a shiver, to Davies, who was laying the breakfast.

‘Well, we can’t do anything till this fog lifts,’ he answered, with a good deal of resignation. Breakfast was a cheerless meal. The damp penetrated to the very cabin, whose roof and walls wept a fine dew. I had dreaded a bathe, and yet missed it, and the ghastly light made the tablecloth look dirtier than it naturally was, and all the accessories more sordid. Something had gone wrong with the bacon, and the lack of egg-cups was not in the least humorous.

Davies was just beginning, in his summary way, to tumble the things together for washing up, when there was a sound of a step on deck, two sea-boots appeared on the ladder, and, before we could wonder who the visitor was, a little man in oilskins and a sou’-wester was stooping towards us in the cabin door, smiling affectionately at Davies out of a round grizzled beard.

‘Well met, captain,’ he said, quietly, in German. ‘Where are you bound to this time?’

‘Bartels!’ exclaimed Davies, jumping up. The two stooping figures, young and old, beamed at one another like father and son.

‘Where have you come from? Have some coffee. How’s the Johannes? Was that you that came in last night? I’m delighted to see you!’ (I spare the reader his uncouth lingo.) The little man was dragged in and seated on the opposite sofa to me.

‘I took my apples to Kappeln,’ he said, sedately, ‘and now I sail to Kiel, and so to Hamburg, where my wife and children are. It is my last voyage of the year. You are no longer alone, captain, I see.’ He had taken off his dripping sou’-wester and was bowing ceremoniously towards me.

‘Oh, I quite forgot!’ said Davies, who had been kneeling on one knee in the low doorway, absorbed in his visitor. ‘This is “meiner Freund,” Herr Carruthers. Carruthers, this is my friend, Schiffer Bartels, of the galliot Johannes.’

Was I never to be at an end of the puzzles which Davies presented to me? All the impulsive heartiness died out of his voice and manner as he uttered the last few words, and there he was, nervously glancing from the visitor to me, like one who, against his will or from tactlessness, has introduced two persons who he knows will disagree.

There was a pause while he fumbled with the cups, poured some cold coffee out and pondered over it as though it were a chemical experiment. Then he muttered something about boiling some more water, and took refuge in the forecastle. I was ill at ease at this period with seafaring men, but this mild little person was easy ground for a beginner. Besides, when he took off his oilskin coat he reminded me less of a sailor than of a homely draper of some country town, with his clean turned-down collar and neatly fitting frieze jacket. We exchanged some polite platitudes about the fog and his voyage last night from Kappeln, which appeared to be a town some fifteen miles up the fiord.

Davies joined in from the forecastle with an excess of warmth which almost took the words out of my mouth. We exhausted the subject very soon, and then my vis-à-vis smiled paternally at me, as he had done at Davies, and said, confidentially:

‘It is good that the captain is no more alone. He is a fine young man—Heaven, what a fine young man! I love him as my son—but he is too brave, too reckless. It is good for him to have a friend.’

I nodded and laughed, though in reality I was very far from being amused.

‘Where was it you met?’ I asked.

‘In an ugly place, and in ugly weather,’ he answered, gravely, but with a twinkle of fun in his eye. ‘But has he not told you?’ he added, with ponderous slyness. ‘I came just in time. No! what am I saying? He is brave as a lion and quick as a cat. I think he cannot drown; but still it was an ugly place and ugly—’

‘What are you talking about, Bartels?’ interrupted Davies, emerging noisily with a boiling kettle.

I answered the question. ‘I was just asking your friend how it was you made his acquaintance.’

‘Oh, he helped me out of a bit of a mess in the North Sea, didn’t you, Bartels?’ he said.

‘It was nothing,’ said Bartels. ‘But the North Sea is no place for your little boat, captain. So I have told you many times. How did you like Flensburg? A fine town, is it not? Did you find Herr Krank, the carpenter? I see you have placed a little mizzen-mast. The rudder was nothing much, but it was well that it held to the Eider. But she is strong and good, your little ship, and—Heaven!—she had need be so.’ He chuckled, and shook his head at Davies as at a wayward child.

This is all the conversation that I need record. For my part I merely waited for its end, determined on my course, which was to know the truth once and for all, and make an end of these distracting mystifications. Davies plied his friend with coffee, and kept up the talk gallantly; but affectionate as he was, his manner plainly showed that he wanted to be alone with me.

The gist of the little skipper’s talk was a parental warning that, though we were well enough here in the ‘Ost-See’, it was time for little boats to be looking for winter quarters. That he himself was going by the Kiel Canal to Hamburg to spend a cosy winter as a decent citizen at his warm fireside, and that we should follow his example. He ended with an invitation to us to visit him on the Johannes, and with suave farewells disappeared into the fog. Davies saw him into his boat, returned without wasting a moment, and sat down on the sofa opposite me.

‘What did he mean?’ I asked.

‘I’ll tell you,’ said Davies, ‘I’ll tell you the whole thing. As far as you’re concerned it’s partly a confession. Last night I had made up my mind to say nothing, but when Bartels turned up I knew it must all come out. It’s been fearfully on my mind, and perhaps you’ll be able to help me. But it’s for you to decide.’

‘Fire away!’ I said.

‘You know what I was saying about the Frisian Islands the other day? A thing happened there which I never told you, when you were asking about my cruise.’

‘It began near Norderney,’ I put in.

‘How did you guess that?’ he asked.

‘You’re a bad hand at duplicity,’ I replied. ‘Go on.’

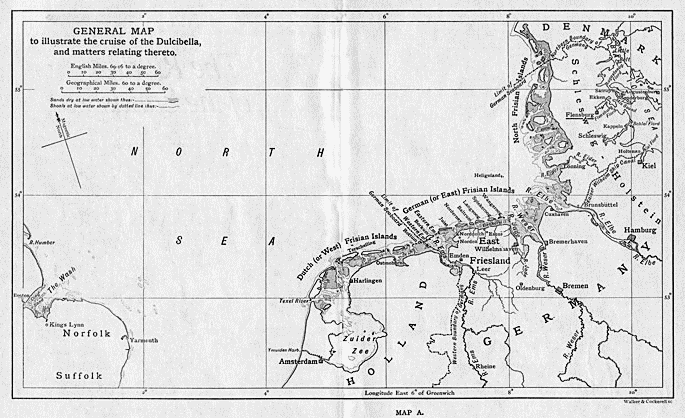

‘Well, you’re quite right, it was there, on 9th September. I told you the sort of thing I was doing at that time, but I don’t think I said that I made inquiries from one or two people about duck-shooting, and had been told by some fishermen at Borkum that there was a big sailing-yacht in those waters, whose owner, a German of the name of Dollmann, shot a good deal, and might give me some tips. Well, I found this yacht one evening, knowing it must be her from the description I had. She was what is called a “barge-yacht”, of fifty or sixty tons, built for shallow water on the lines of a Dutch galliot, with lee-boards and those queer round bows and square stern. She’s something like those galliots anchored near us now. You sometimes see the same sort of yacht in English waters, only there they copy the Thames barges. She looked a clipper of her sort, and very smart; varnished all over and shining like gold. I came on her about sunset, after a long day of exploring round the Ems estuary. She was lying in—’

‘Wait a bit, let’s have the chart,’ I interrupted.

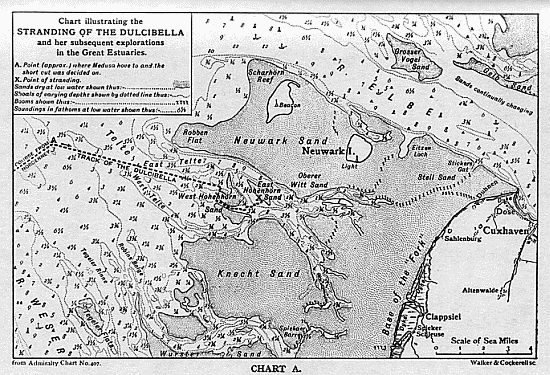

Davies found it and spread it on the table between us, first pushing back the cloth and the breakfast things to one end, where they lay in a slovenly litter. This was one of the only two occasions on which I ever saw him postpone the rite of washing up, and it spoke volumes for the urgency of the matter in hand.

‘Here it is,’ said Davies [See Map A] and I looked with a new and strange interest at the long string of slender islands, the parallel line of coast, and the confusion of shoals, banks, and channels which lay between. ‘Here’s Norderney, you see. By the way, there’s a harbour there at the west end of the island, the only real harbour on the whole line of islands, Dutch or German, except at Terschelling. There’s quite a big town there, too, a watering place, where Germans go for sea-bathing in the summer. Well, the Medusa, that was her name, was lying in the Riff Gat roadstead, flying the German ensign, and I anchored for the night pretty near her. I meant to visit her owner later on, but I very nearly changed my mind, as I always feel rather a fool on smart yachts, and my German isn’t very good. However, I thought I might as well; so, after dinner, when it was dark, I sculled over in the dinghy, hailed a sailor on deck, said who I was, and asked if I could see the owner. The sailor was a surly sort of chap, and there was a good long delay while I waited on deck, feeling more and more uncomfortable. Presently a steward came up and showed me down the companion and into the saloon, which, after this, looked—well, horribly gorgeous—you know what I mean, plush lounges, silk cushions, and that sort of thing. Dinner seemed to be just over, and wine and fruit were on the table. Herr Dollmann was there at his coffee. I introduced myself somehow—’

‘Stop a moment,’ I said; ‘what was he like?’

‘Oh, a tall, thin chap, in evening dress; about fifty I suppose, with greyish hair and a short beard. I’m not good at describing people. He had a high, bulging forehead, and there was something about him—but I think I’d better tell you the bare facts first. I can’t say he seemed pleased to see me, and he couldn’t speak English, and, in fact, I felt infernally awkward. Still, I had an object in coming, and as I was there I thought I might as well gain it.’

The notion of Davies in his Norfolk jacket and rusty flannels haranguing a frigid German in evening dress in a ‘gorgeous’ saloon tickled my fancy greatly.

‘He seemed very much astonished to see me; had evidently seen the Dulcibella arrive, and had wondered what she was. I began as soon as I could about the ducks, but he shut me up at once, said I could do nothing hereabouts. I put it down to sportsman’s jealousy—you know what that is. But I saw I had come to the wrong shop, and was just going to back out and end this unpleasant interview, when he thawed a bit, offered me some wine, and began talking in quite a friendly way, taking a great interest in my cruise and my plans for the future. In the end we sat up quite late, though I never felt really at my ease. He seemed to be taking stock of me all the time, as though I were some new animal.’ (How I sympathized with that German!) ‘We parted civilly enough, and I rowed back and turned in, meaning to potter on eastwards early next day.

‘But I was knocked up at dawn by a sailor with a message from Dollmann asking if he could come to breakfast with me. I was rather flabbergasted, but didn’t like to be rude, so I said, “Yes.” Well, he came, and I returned the call—and—well, the end of it was that I stayed at anchor there for three days.’ This was rather abrupt.

‘How did you spend the time?’ I asked. Stopping three days anywhere was an unusual event for him, as I knew from his log.

‘Oh, I lunched or dined with him once or twice—with them, I ought to say,’ he added, hurriedly. ‘His daughter was with him. She didn’t appear the evening I first called.’

‘And what was she like?’ I asked, promptly, before he could hurry on.

‘Oh, she seemed a very nice girl,’ was the guarded reply, delivered with particular unconcern, ‘and—the end of it was that I and the Medusa sailed away in company. I must tell you how it came about, just in a few words for the present.

‘It was his suggestion. He said he had to sail to Hamburg, and proposed that I should go with him in the Dulcibella as far as the Elbe, and then, if I liked, I could take the ship canal at Brunsbüttel through to Kiel and the Baltic. I had no very fixed plans of my own, though I had meant to go on exploring eastwards between the islands and the coast, and so reach the Elbe in a much slower way. He dissuaded me from this, sticking to it that I should have no chance of ducks, and urging other reasons. Anyway, we settled to sail in company direct to Cuxhaven, in the Elbe. With a fair wind and an early start it should be only one day’s sail of about sixty miles.

‘The plan only came to a head on the evening of the third day, 12th September.

‘I told you, I think, that the weather had broken after a long spell of heat. That very day it had been blowing pretty hard from the west, and the glass was falling still. I said, of course, that I couldn’t go with him if the weather was too bad, but he prophesied a good day, said it was an easy sail, and altogether put me on my mettle. You can guess how it was. Perhaps I had talked about single-handed cruising as though it were easier than it was, though I never meant it in a boasting way, for I hate that sort of thing, and besides there is no danger if you’re careful—’

‘Oh, go on,’ I said.

‘Anyway, we went next morning at six. It was a dirty-looking day, wind W.N.W., but his sails were going up and mine followed. I took two reefs in, and we sailed out into the open and steered E.N.E. along the coast for the Outer Elbe Lightship about fifty knots off. Here it all is, you see.’ (He showed me the course on the chart.) ‘The trip was nothing for his boat, of course, a safe, powerful old tub, forging through the sea as steady as a house. I kept up with her easily at first. My hands were pretty full, for there was a hard wind on my quarter and a troublesome sea; but as long as nothing worse came I knew I should be all right, though I also knew that I was a fool to have come.

‘All went well till we were off Wangeroog, the last of the islands—here—and then it began to blow really hard. I had half a mind to chuck it and cut into the Jade River, down there,’ but I hadn’t the face to, so I hove to and took in my last reef.’ (Simple words, simply uttered; but I had seen the operation in calm water and shuddered at the present picture.) ‘We had been about level till then, but with my shortened canvas I fell behind. Not that that mattered in the least. I knew my course, had read up my tides, and, thick as the weather was, I had no doubt of being able to pick up the lightship. No change of plan was possible now. The Weser estuary was on my starboard hand, but the whole place was a lee-shore and a mass of unknown banks—just look at them. I ran on, the Dulcibella doing her level best, but we had some narrow shaves of being pooped. I was about here, say six miles south-west of the lightship, [See Chart A] when I suddenly saw that the Medusa had hove to right ahead, as though waiting till I came up. She wore round again on the course as I drew level, and we were alongside for a bit. Dollmann lashed the wheel, leaned over her quarter, and shouted, very slowly and distinctly so that I could understand; “Follow me—sea too bad for you outside—short cut through sands—save six miles.”

‘It was taking me all my time to manage the tiller, but I knew what he meant at once, for I had been over the chart carefully the night before. [See Map A] You see, the whole bay between Wangeroog and the Elbe is encumbered with sand. A great jagged chunk of it runs out from Cuxhaven in a north-westerly direction for fifteen miles or so, ending in a pointed spit, called the Scharhorn. To reach the Elbe from the west you have to go right outside this, round the lightship, which is off the Scharhorn, and double back. Of course, that’s what all big vessels do. But, as you see, these sands are intersected here and there by channels, very shallow and winding, exactly like those behind the Frisian Islands. Now look at this one, which cuts right through the big chunk of sand and comes out near Cuxhaven. The Telte [See Chart A] it’s called. It’s miles wide, you see, at the entrance, but later on it is split into two by the Hohenhörn bank: then it gets shallow and very complicated, and ends in a mere tidal driblet with another name. It’s just the sort of channel I should like to worry into on a fine day or with an off-shore wind. Alone, in thick weather and a heavy sea, it would have been folly to attempt it, except as a desperate resource. But, as I said I knew at once that Dollmann was proposing to run for it and guide me in.

‘I didn’t like the idea, because I like doing things for myself, and, silly as it sounds, I believe I resented being told the sea was too bad for me, which it certainly was. Yet the short cut did save several miles and a devil of a tumble off the Scharhorn, where two tides meet. I had complete faith in Dollmann, and I suppose I decided that I should be a fool not to take a good chance. I hesitated. I know; but in the end I nodded, and held up my arm as she forged ahead again. Soon after, she shifted her course and I followed. You asked me once if I ever took a pilot. That was the only time.’

He spoke with bitter gravity, flung himself back, and felt his pipe. It was not meant for a dramatic pause, but it certainly was one. I had just a glimpse of still another Davies—a Davies five years older throbbing with deep emotions, scorn, passion, and stubborn purpose; a being above my plane, of sterner stuff, wider scope. Intense as my interest had become, I waited almost timidly while he mechanically rammed tobacco into his pipe and struck ineffectual matches. I felt that whatever the riddle to be solved, it was no mean one. He repressed himself with an effort, half rose, and made his circular glance at the clock, barometer, and skylight, and then resumed.

‘We soon came to what I knew must be the beginning of the Telte channel. All round you could hear the breakers on the sands, though it was too thick to see them yet. As the water shoaled, the sea, of course, got shorter and steeper. There was more wind—a whole gale I should say.

‘I kept dead in the wake of the Medusa, but to my disgust I found she was gaining on me very fast. Of course I had taken for granted, when he said he would lead me in, that he would slow down and keep close to me. He could easily have done so by getting his men up to check his sheets or drop his peak. Instead of that he was busting on for all he was worth. Once, in a rain-squall, I lost sight of him altogether; got him faintly again, but had enough to do with my own tiller not to want to be peering through the scud after a runaway pilot. I was all right so far, but we were fast approaching the worst part of the whole passage, where the Hohenhörn bank blocks the road, and the channel divides. I don’t know what it looks like to you on the chart—perhaps fairly simple, because you can follow the twists of the channels, as on a ground-plan; but a stranger coming to a place like that (where there are no buoys, mind you) can tell nothing certain by the eye—unless perhaps at dead low water, when the banks are high and dry, and in very clear weather—he must trust to the lead and the compass, and feel his way step by step. I knew perfectly well that what I should soon see would be a wall of surf stretching right across and on both sides. To feel one’s way in that sort of weather is impossible. You must know your way, or else have a pilot. I had one, but he was playing his own game.

‘With a second hand on board to steer while I conned I should have felt less of an ass. As it was, I knew I ought to be facing the music in the offing, and cursed myself for having broken my rule and gone blundering into this confounded short cut. It was giving myself away, doing just the very thing that you can’t do in single-handed sailing.

‘By the time I realized the danger it was far too late to turn and hammer out to the open. I was deep in the bottle-neck bight of the sands, jammed on a lee shore, and a strong flood tide sweeping me on. That tide, by the way, gave just the ghost of a chance. I had the hours in my head, and knew it was about two-thirds flood, with two hours more of rising water. That meant the banks would be all covering when I reached them, and harder than ever to locate; but it also meant that I might float right over the worst of them if I hit off a lucky place.’ Davies thumped the table in disgust. ‘Pah! It makes me sick to think of having to trust to an accident like that, like a lubberly cockney out for a boozy Bank Holiday sail. Well, just as I foresaw, the wall of surf appeared clean across the horizon, and curling back to shut me in, booming like thunder. When I last saw the Medusa she seemed to be charging it like a horse at a fence, and I took a rough bearing of her position by a hurried glance at the compass. At that very moment I thought she seemed to luff and show some of her broadside; but a squall blotted her out and gave me hell with the tiller. After that she was lost in the white mist that hung over the line of breakers. I kept on my bearing as well as I could, but I was already out of the channel. I knew that by the look of the water, and as we neared the bank I saw it was all awash and without the vestige of an opening. I wasn’t going to chuck her on to it without an effort; so, more by instinct than with any particular hope, I put the helm down, meaning to work her along the edge on the chance of spotting a way over. She was buried at once by the beam sea, and the jib flew to blazes; but the reefed stays’l stood, she recovered gamely, and I held on, though I knew it could only be for a few minutes, as the centre-plate was up, and she made frightful leeway towards the bank.

‘I was half-blinded by scud, but suddenly I noticed what looked like a gap, behind a spit which curled out right ahead. I luffed still more to clear this spit, but she couldn’t weather it. Before you could say knife she was driving across it, bumped heavily, bucked forward again, bumped again, and—ripped on in deeper water! I can’t describe the next few minutes. I was in some sort of channel, but a very narrow one, and the sea broke everywhere. I hadn’t proper command either; for the rudder had crocked up somehow at the last bump. I was like a drunken man running for his life down a dark alley, barking himself at every corner. It couldn’t last long, and finally we went crash on to something and stopped there, grinding and banging. So ended that little trip under a pilot.

‘Well, it was like this—there was really no danger’—I opened my eyes at the characteristic phrase. ‘I mean, that lucky stumble into a channel was my salvation. Since then I had struggled through a mile of sands, all of which lay behind me like a breakwater against the gale. They were covered, of course, and seething like soapsuds; but the force of the sea was deadened. The Dulce was bumping, but not too heavily. It was nearing high tide, and at half ebb she would be high and dry.

‘In the ordinary way I should have run out a kedge with the dinghy, and at the next high water sailed farther in and anchored where I could lie afloat. The trouble was now that my hand was hurt and my dinghy stove in, not to mention the rudder business. It was the first bump on the outer edge that did the damage. There was a heavy swell there, and when we struck, the dinghy, which was towing astern, came home on her painter and down with a crash on the yacht’s weather quarter. I stuck out one hand to ward it off and got it nipped on the gunwale. She was badly stove in and useless, so I couldn’t run out the kedge’—this was Greek to me, but I let him go on—’and for the present my hand was too painful even to stow the boom and sails, which were whipping and racketing about anyhow. There was the rudder, too, to be mended; and we were several miles from the nearest land. Of course, if the wind fell, it was all easy enough; but if it held or increased it was a poor look-out. There’s a limit to strain of that sort—and other things might have happened.

‘In fact, it was precious lucky that Bartels turned up. His galliot was at anchor a mile away, up a branch of the channel. In a clear between squalls he saw us, and, like a brick, rowed his boat out—he and his boy, and a devil of a pull they must have had. I was glad enough to see them—no, that’s not true; I was in such a fury of disgust and shame that I believe I should have been idiot enough to say I didn’t want help, if he hadn’t just nipped on board and started work. He’s a terror to work, that little mouse of a chap. In half an hour he had stowed the sails, unshackled the big anchor, run out fifty fathoms of warp, and hauled her off there and then into deep water. Then they towed her up the channel—it was dead to leeward and an easy job—and berthed her near their own vessel. It was dark by that time, so I gave them a drink, and said good-night. It blew a howling gale that night, but the place was safe enough, with good ground-tackle.

‘The whole affair was over; and after supper I thought hard about it all.’

——————————

VIII.

The Theory

DAVIES leaned back and gave a deep sigh, as though he still felt the relief from some tension. I did the same, and felt the same relief. The chart, freed from the pressure of our fingers, rolled up with a flip, as though to say, ‘What do you think of that?’ I have straightened out his sentences a little, for in the excitement of his story they had grown more and more jerky and elliptical.

‘What about Dollmann?’ I asked.

‘Of course,’ said Davies, ‘what about him? I didn’t get at much that night. It was all so sudden. The only thing I could have sworn to from the first was that he had purposely left me in the lurch that day. I pieced out the rest in the next few days, which I’ll just finish with as shortly as I can. Bartels came aboard next morning, and though it was blowing hard still we managed to shift the Dulcibella to a place where she dried safely at the mid-day low water, and we could get at her rudder. The lower screw-plate on the stern post had wrenched out, and we botched it up roughly as a make-shift. There were other little breakages, but nothing to matter, and the loss of the jib was nothing, as I had two spare ones. The dinghy was past repair just then, and I lashed it on deck.

‘It turned out that Bartels was carrying apples from Bremen to Kappeln (in this fiord), and had run into that channel in the sands for shelter from the weather. To-day he was bound for the Eider River, whence, as I told you, you can get through (by river and canal) into the Baltic. Of course the Elbe route, by the new Kaiser Wilhelm Ship Canal, is the shortest. The Eider route is the old one, but he hoped to get rid of some of his apples at Tönning, the town at its mouth. Both routes touch the Baltic at Kiel. As you know, I had been running for the Elbe, but yesterday’s muck-up put me off, and I changed my mind—I’ll tell you why presently—and decided to sail to the Eider along with the Johannes and get through that way. It cleared from the east next day, and I raced him there, winning hands down, left him at Tönning, and in three days was in the Baltic. It was just a week after I ran ashore that I wired to you. You see, I had come to the conclusion that that chap was a spy.’

In the end it came out quite quietly and suddenly, and left me in profound amazement. ‘I wired to you—that chap was a spy.’ It was the close association of these two ideas that hit me hardest at the moment. For a second I was back in the dreary splendour of the London club-room, spelling out that crabbed scrawl from Davies, and fastidiously criticizing its proposal in the light of a holiday. Holiday! What was to be its issue? Chilling and opaque as the fog that filtered through the skylight there flooded my imagination a mist of doubt and fear.

‘A spy!’ I repeated blankly. ‘What do you mean? Why did you wire to me? A spy of what—of whom?’

‘I’ll tell you how I worked it out,’ said Davies. ‘I don’t think “spy” is the right word; but I mean something pretty bad.

‘He purposely put me ashore. I don’t think I’m suspicious by nature, but I know something about boats and the sea. I know he could have kept close to me if he had chosen, and I saw the whole place at low water when we left those sands on the second day. Look at the chart again. Here’s the Hohenhörn bank that I showed you as blocking the road. [See Chart A] It’s in two pieces—first the west and then the east. You see the Telte channel dividing into two branches and curving round it. Both branches are broad and deep, as channels go in those waters. Now, in sailing in I was nowhere near either of them. When I last saw Dollmann he must have been steering straight for the bank itself, at a point somewhere here, quite a mile from the northern arm of the channel, and two from the southern. I followed by compass, as you know, and found nothing but breakers ahead. How did I get through? That’s where the luck came in. I spoke of only two channels, that is, round the bank—one to the north, the other to the south. But look closely and you’ll see that right through the centre of the West Hohenhörn runs another, a very narrow and winding one, so small that I hadn’t even noticed it the night before, when I was going over the chart. That was the one I stumbled into in that tailor’s fashion, as I was groping along the edge of the surf in a desperate effort to gain time. I bolted down it blindly, came out into this strip of open water, crossed that aimlessly, and brought up on the edge of the East Hohenhörn, here. It was more than I deserved. I can see now that it was a hundred to one in favour of my striking on a bad place outside, where I should have gone to pieces in three minutes.’

‘And how did Dollmann go?’ I asked.

‘It’s as clear as possible,’ Davies answered. ‘He doubled back into the northern channel when he had misled me enough. Do you remember my saying that when I last saw him I thought he had luffed and showed his broadside? I had another bit of luck in that. He was luffing towards the north—so it struck me through the blur—and when I in my turn came up to the bank, and had to turn one way or the other to avoid it, I think I should naturally have turned north too, as he had done. In that case I should have been done for, for I should have had a mile of the bank to skirt before reaching the north channel, and should have driven ashore long before I got there. But as a matter of fact I turned south.’

‘Why?’

‘Couldn’t help it. I was running on the starboard tack—boom over to port; to turn north would have meant a jibe, and as things were I couldn’t risk one. It was blowing like fits; if anything had carried away I should have been on shore in a jiffy. I scarcely thought about it at all, but put the helm down and turned her south. Though I knew nothing about it, that little central channel was now on my port hand, distant about two cables. The whole thing was luck from beginning to end.’

Helped by pluck, I thought to myself, as I tried with my landsman’s fancy to conjure up that perilous scene. As to the truth of the affair, the chart and Davies’s version were easy enough to follow, but I felt only half convinced. The ‘spy’, as Davies strangely called his pilot, might have honestly mistaken the course himself, outstripped his convoy inadvertently, and escaped disaster as narrowly as she did. I suggested this on the spur of the moment, but Davies was impatient.

‘Wait till you hear the whole thing,’ he said. ‘I must go back to when I first met him. I told you that on that first evening he began by being as rude as a bear and as cold as stone, and then became suddenly friendly. I can see now that in the talk that followed he was pumping me hard. It was an easy game to play, for I hadn’t seen a gentleman since Morrison left me, I was tremendously keen about my voyage, and I thought the chap was a good sportsman, even if he was a bit dark about the ducks. I talked quite freely—at least, as freely as I could with my bad German—about my last fortnight’s sailing; how I had been smelling out all the channels in and out of the islands, how interested I had been in the whole business, puzzling out the effect of the winds on the tides, the set of the currents, and so on. I talked about my difficulties, too; the changes in the buoys, the prehistoric rottenness of the English charts. He drew me out as much as he could, and in the light of what followed I can see the point of scores of his questions.

‘The next day and the next I saw a good deal of him, and the same thing went on. And then there were my plans for the future. My idea was, as I told you, to go on exploring the German coast just as I had the Dutch. His idea—Heavens, how plainly I see it now!—was to choke me off, get me to clear out altogether from that part of the coast. That was why he said there were no ducks. That was why he cracked up the Baltic as a cruising-ground and shooting-ground. And that was why he broached and stuck to that plan of sailing in company direct to the Elbe. It was to see me clear.

‘He improved on that.’

‘Yes, but after that, it’s guess-work. I mean that I can’t tell when he first decided to go one better and drown me. He couldn’t count for certain on bad weather, though he held my nose to it when it came. But, granted that he wanted to get rid of me altogether, he got a magnificent chance on that trip to the Elbe lightship. I expect it struck him suddenly, and he acted on the impulse. Left to myself I was all right; but the short cut was a grand idea of his. Everything was in its favour—wind, sea, sand, tide. He thinks I’m dead.’

‘But the crew?’ I said; ‘what about the crew?’

‘That’s another thing. When he first hove to, waiting for me, of course they were on deck (two of them, I think) hauling at sheets. But by the time I had drawn up level the Medusa had worn round again on her course, and no one was on deck but Dollmann at the wheel. No one overheard what he said.’

‘Wouldn’t they have seen you again?’

‘Very likely not; the weather was very thick, and the Dulce is very small.’

The incongruity of the whole business was striking me. Why should anyone want to kill Davies, and why should Davies, the soul of modesty and simplicity, imagine that anyone wanted to kill him? He must have cogent reasons, for he was the last man to give way to a morbid fancy.

‘Go on,’ I said. ‘What was his motive? A German finds an Englishman exploring a bit of German coast, determines to stop him, and even to get rid of him. It looks so far as if you were thought to be the spy.

Davies winced. ‘But he’s not a German,’ he said, hotly. ‘He’s an Englishman.’

‘An Englishman?’

‘Yes, I’m sure of it. Not that I’ve much to go on. He professed to know very little English, and never spoke it, except a word or two now and then to help me out of a sentence; and as to his German, he seemed to me to speak it like a native; but, of course, I’m no judge.’ Davies sighed. ‘That’s where I wanted someone like you. You would have spotted him at once, if he wasn’t German. I go more by a—what do you call it?—a—’

‘General impression,’ I suggested.

‘Yes, that’s what I mean. It was something in his looks and manner; you know how different we are from foreigners. And it wasn’t only himself, it was the way he talked—I mean about cruising and the sea, especially. It’s true he let me do most of the talking; but, all the same—how can I explain it? I felt we understood one another, in a way that two foreigners wouldn’t.

‘He pretended to think me a bit crazy for coming so far in a small boat, but I could swear he knew as much about the game as I did; for lots of little questions he asked had the right ring in them. Mind you, all this is an afterthought. I should never have bothered about it—I’m not cut out for a Sherlock Holmes—if it hadn’t been for what followed.’

‘It’s rather vague,’ I said. ‘Have you no more definite reason for thinking him English?’

‘There were one or two things rather more definite,’ said Davies, slowly. ‘You know when he hove to and hailed me, proposing the short cut, I told you roughly what he said. I forget the exact words, but “abschneiden” came in—”durch Watten” and “abschneiden” (they call the banks “watts”, you know); they were simple words, and he shouted them loud, so as to carry through the wind. I understood what he meant, but, as I told you, I hesitated before consenting. I suppose he thought I didn’t understand, for just as he was drawing ahead again he pointed to the suth’ard, and then shouted through his hands as a trumpet “Verstehen Sie? short-cut through sands; follow me!” the last two sentences in downright English. I can hear those words now, and I’ll swear they were in his native tongue. Of course I thought nothing of it at the time. I was quite aware that he knew a few English words, though he had always mis-pronounced them; an easy trick when your hearer suspects nothing. But I needn’t say that just then I was observant of trifles. I don’t pretend to be able to unravel a plot and steer a small boat before a heavy sea at the same moment.’

‘And if he was piloting you into the next world he could afford to commit himself before you parted! Was there anything else? By the way, how did the daughter strike you? Did she look English too?’

Two men cannot discuss a woman freely without a deep foundation of intimacy, and, until this day, the subject had never arisen between us in any form. It was the last that was likely to, for I could have divined that Davies would have met it with an armour of reserve. He was busy putting on this armour now; yet I could not help feeling a little brutal as I saw how badly he jointed his clumsy suit of mail. Our ages were the same, but I laugh now to think how old and blasé I felt as the flush warmed his brown skin, and he slowly propounded the verdict, ‘Yes, I think she did.’

‘She talked nothing but German, I suppose?’

‘Oh, of course.’

‘Did you see much of her?’

‘A good deal.’

‘Was she—,’ (how frame it?) ‘Did she want you to sail to the Elbe with them?’

‘She seemed to,’ admitted Davies, reluctantly, clutching at his ally, the match-box. ‘But, hang it, don’t dream that she knew what was coming,’ he added, with sudden fire.

I pondered and wondered, shrinking from further inquisition, easy as it would have been with so truthful a victim, and banishing all thought of ill-timed chaff. There was a cross-current in this strange affair, whose depth and strength I was beginning to gauge with increasing seriousness. I did not know my man yet, and I did not know myself. A conviction that events in the near future would force us into complete mutual confidence withheld me from pressing him too far. I returned to the main question; who was Dollmann, and what was his motive? Davies struggled out of his armour.

‘I’m convinced,’ he said, ‘that he’s an Englishman in German service. He must be in German service, for he had evidently been in those waters a long time, and knew every inch of them; of course, it’s a very lonely part of the world, but he has a house on Norderney Island; and he, and all about him, must be well known to a certain number of people. One of his friends I happened to meet; what do you think he was? A naval officer. It was on the afternoon of the third day, and we were having coffee on the deck of the Medusa, and talking about next day’s trip, when a little launch came buzzing up from seaward, drew alongside, and this chap I’m speaking of came on board, shook hands with Dollmann, and stared hard at me. Dollmann introduced us, calling him Commander von Brüning, in command of the torpedo gunboat Blitz. He pointed towards Norderney, and I saw her—a low, grey rat of a vessel—anchored in the Roads about two miles away. It turned out that she was doing the work of fishery guardship on that part of the coast.

‘I must say I took to him at once. He looked a real good sort, and a splendid officer, too—just the sort of chap I should have liked to be. You know I always wanted—but that’s an old story, and can wait. I had some talk with him, and we got on capitally as far as we went, but that wasn’t far, for I left pretty soon, guessing that they wanted to be alone.’

‘Were they alone then?’ I asked, innocently.

‘Oh, Fräulein Dollmann was there, of course,’ explained Davies, feeling for his armour again.

‘Did he seem to know them well?’ I pursued, inconsequently.

‘Oh, yes, very well.’

Scenting a faint clue, I felt the need of feminine weapons for my sensitive antagonist. But the opportunity passed.

‘That was the last I saw of him,’ he said. ‘We sailed, as I told you, at daybreak next morning. Now, have you got any idea what I’m driving at?’

‘A rough idea,’ I answered. ‘Go ahead.’

Davies sat up to the table, unrolled the chart with a vigorous sweep of his two hands, and took up his parable with new zest.

‘I start with two certainties,’ he said. ‘One is that I was “moved on” from that coast, because I was too inquisitive. The other is that Dollmann is at some devil’s work there which is worth finding out. Now’—he paused in a gasping effort to be logical and articulate. ‘Now—well, look at the chart. No, better still, look first at this map of Germany. It’s on a small scale, and you can see the whole thing.’ He snatched down a pocket-map from the shelf and unfolded it. [See Map A] ‘Here’s this huge empire, stretching half over central Europe—an empire growing like wildfire, I believe, in people, and wealth, and everything. They’ve licked the French, and the Austrians, and are the greatest military power in Europe. I wish I knew more about all that, but what I’m concerned with is their sea-power. It’s a new thing with them, but it’s going strong, and that Emperor of theirs is running it for all it’s worth. He’s a splendid chap, and anyone can see he’s right. They’ve got no colonies to speak of, and must have them, like us. They can’t get them and keep them, and they can’t protect their huge commerce without naval strength. The command of the sea is the thing nowadays, isn’t it? I say, don’t think these are my ideas,’ he added, naively. ‘It’s all out of Mahan and those fellows. Well, the Germans have got a small fleet at present, but it’s a thundering good one, and they’re building hard. There’s the—and the—.’ He broke off into a digression on armaments and speeds in which I could not follow him. He seemed to know every ship by heart. I had to recall him to the point. ‘Well, think of Germany as a new sea-power,’ he resumed. ‘The next thing is, what is her coast-line? It’s a very queer one, as you know, split clean in two by Denmark, most of it lying east of that and looking on the Baltic, which is practically an inland sea, with its entrance blocked by Danish islands. It was to evade that block that William built the ship canal from Kiel to the Elbe, but that could be easily smashed in war-time. Far the most important bit of coast-line is that which lies west of Denmark and looks on the North Sea. It’s there that Germany gets her head out into the open, so to speak. It’s there that she fronts us and France, the two great sea-powers of Western Europe, and it’s there that her greatest ports are and her richest commerce.

‘Now it must strike you at once that it’s ridiculously short compared with the huge country behind it. From Borkum to the Elbe, as the crow flies, is only seventy miles. Add to that the west coast of Schleswig, say 120 miles. Total, say, two hundred. Compare that with the seaboard of France and England. Doesn’t it stand to reason that every inch of it is important? Now what sort of coast is it? Even on this small map you can see at once, by all those wavy lines, shoals and sand everywhere, blocking nine-tenths of the land altogether, and doing their best to block the other tenth where the great rivers run in. Now let’s take it bit by bit. You see it divides itself into three. Beginning from the west the first piece is from Borkum to Wangeroog—fifty odd miles. What’s that like? A string of sandy islands backed by sand; the Ems river at the western end, on the Dutch border, leading to Emden—not much of a place. Otherwise, no coast towns at all. Second piece: a deep sort of bay consisting of the three great estuaries—the Jade, the Weser, and the Elbe—leading to Wilhelmshaven (their North Sea naval base), Bremen, and Hamburg. Total breadth of bay twenty odd miles only; sandbanks littered about all through it. Third piece: the Schleswig coast, hopelessly fenced in behind a six to eight mile fringe of sand. No big towns; one moderate river, the Eider. Let’s leave that third piece aside. I may be wrong, but, in thinking this business out, I’ve pegged away chiefly at the other two, the seventy-mile stretch from Borkum to the Elbe—half of it estuaries, and half islands. It was there that I found the Medusa, and it’s that stretch that, thanks to him, I missed exploring.’

I made an obvious conjecture. ‘I suppose there are forts and coast defences? Perhaps he thought you would see too much. By the way, he saw your naval books, of course?’

‘Exactly. Of course that was my first idea; but it can’t be that. It doesn’t explain things in the least. To begin with, there are no forts and can be none in that first division, where the islands are. There might be something on Borkum to defend the Ems; but it’s very unlikely, and, anyway, I had passed Borkum and was at Norderney. There’s nothing else to defend. Of course it’s different in the second division, where the big rivers are. There are probably hosts of forts and mines round Wilhelmshaven and Bremerhaven, and at Cuxhaven just at the mouth of the Elbe. Not that I should ever dream of bothering about them; every steamer that goes in would see as much as me. Personally, I much prefer to stay on board, and don’t often go on shore. And, good Heavens!’ (Davies leant back and laughed joyously) ‘do I look like that kind of spy?’

I figured to myself one of those romantic gentlemen that one reads of in sixpenny magazines, with a Kodak in his tie-pin, a sketch-book in the lining of his coat, and a selection of disguises in his hand luggage. Little disposed for merriment as I was, I could not help smiling, too.

‘About this coast,’ resumed Davies. ‘In the event of war it seems to me that every inch of it would be important, sand and all. Take the big estuaries first, which, of course, might be attacked or blockaded by an enemy. At first sight you would say that their main channels were the only things that mattered. Now, in time of peace there’s no secrecy about the navigation of these. They’re buoyed and lighted like streets, open to the whole world, and taking an immense traffic; well charted, too, as millions of pounds in commerce depend on them. But now look at the sands they run through, intersected, as I showed you, by threads of channels, tidal for the most part, and probably only known to smacks and shallow coasters, like that galliot of Bartels.

‘It strikes me that in a war a lot might depend on these, both in defence and attack, for there’s plenty of water in them at the right tide for patrol-boats and small torpedo craft, though I can see they take a lot of knowing. Now, say we were at war with Germany—both sides could use them as lines between the three estuaries; and to take our own case, a small torpedo-boat (not a destroyer, mind you) could on a dark night cut clean through from the Jade to the Elbe and play the deuce with the shipping there. But the trouble is that I doubt if there’s a soul in our fleet who knows those channels. We haven’t coasters there; and, as to yachts, it’s a most unlikely game for an English yacht to play at; but it does so happen that I have a fancy for that sort of thing and would have explored those channels in the ordinary course.’ I began to see his drift.

‘Now for the islands. I was rather stumped there at first, I grant, because, though there are lashings of sand behind them, and the same sort of intersecting channels, yet there seems nothing important to guard or attack.

‘Why shouldn’t a stranger ramble as he pleases through them? Still Dollmann had his headquarters there, and I was sure that had some meaning. Then it struck me that the same point held good, for that strip of Frisian coast adjoins the estuaries, and would also form a splendid base for raiding midgets, which could travel unseen right through from the Ems to the Jade, and so to the Elbe, as by a covered way between a line of forts.

‘Now here again it’s an unknown land to us. Plenty of local galliots travel it, but strangers never, I should say. Perhaps at the most an occasional foreign yacht gropes in at one of the gaps between the islands for shelter from bad weather, and is precious lucky to get in safe. Once again, it was my fad to like such places, and Dollmann cleared me out. He’s not a German, but he’s in with Germans, and naval Germans too. He’s established on that coast, and knows it by heart. And he tried to drown me. Now what do you think?’ He gazed at me long and anxiously.

———————–

A note from Boathouse:

It’s going to be a long winter and winter for most is a season to research and plan upcoming trips, day dream about boating and also read about boating. Presented here a chapter of ‘The Riddle of the sands’ an excellent pre WWI sailing adventure. Every week Boathouse will present a chapter or two of this public domain work and hopefully this will ease the passage of winter for our readers. If you are inpatient and can’t wait for each weeks installment you can read the entire book at gutenburg.org If you would rather listen to the book here is a link to an audio version: Chapter 5 & Chapter 6

If you would like to be notified when posts are added to this blog please send an email to blogadmin@boathouse.ca with the words ‘Subscribe to blog’ as the subject.

Have fun! Post a comment, let us know what you think.

Boathouse

—————————————————————-

V.

Wanted, a North Wind

NOTHING disturbed my rest that night, so adaptable is youth and so masterful is nature. At times I was remotely aware of a threshing of rain and a humming of wind, with a nervous kicking of the little hull, and at one moment I dreamt I saw an apparition by candle-light of Davies, clad in pyjamas and huge top-boots, grasping a misty lantern of gigantic proportions. But the apparition mounted the ladder and disappeared, and I passed to other dreams.

A blast in my ear, like the voice of fifty trombones, galvanized me into full consciousness. The musician, smiling and tousled, was at my bedside, raising a foghorn to his lips with deadly intention. ‘It’s a way we have in the Dulcibella,’ he said, as I started up on one elbow. ‘I didn’t startle you much, did I?’ he added.

‘Well, I like the mattinata better than the cold douche,’ I answered, thinking of yesterday.

‘Fine day and magnificent breeze!’ he answered. My sensations this morning were vastly livelier than those of yesterday at the same hour. My limbs were supple again and my head clear. Not even the searching wind could mar the ecstasy of that plunge down to smooth, seductive sand, where I buried greedy fingers and looked through a medium blue, with that translucent blue, fairy-faint and angel-pure, that you see in perfection only in the heart of ice. Up again to sun, wind, and the forest whispers from the shore; down just once more to see the uncouth anchor stabbing the sand’s soft bosom with one rusty fang, deaf and inert to the Dulcibella‘s puny efforts to drag him from his prey. Back, holding by the cable as a rusty clue from heaven to earth, up to that bourgeois little maiden’s bows; back to breakfast, with an appetite not to be blunted by condensed milk and somewhat passé bread. An hour later we had dressed the Dulcibella for the road, and were foaming into the grey void of yesterday, now a noble expanse of wind-whipped blue, half surrounded by distant hills, their every outline vivid in the rain-washed air.

I cannot pretend that I really enjoyed this first sail into the open, though I was keenly anxious to do so. I felt the thrill of those forward leaps, heard that persuasive song the foam sings under the lee-bow, saw the flashing harmonies of sea and sky; but sensuous perception was deadened by nervousness. The yacht looked smaller than ever outside the quiet fiord. The song of the foam seemed very near, the wave crests aft very high. The novice in sailing clings desperately to the thoughts of sailors—effective, prudent persons, with a typical jargon and a typical dress, versed in local currents and winds. I could not help missing this professional element. Davies, as he sat grasping his beloved tiller, looked strikingly efficient in his way, and supremely at home in his surroundings; but he looked the amateur through and through, as with one hand, and (it seemed) one eye, he wrestled with a spray-splashed chart half unrolled on the deck beside him. All his casual ways returned to me—his casual talk and that last adventurous voyage to the Baltic, and the suspicions his reticence had aroused.

‘Do you see a monument anywhere?’ he said, all at once; and, before I could answer; ‘We must take another reef.’ He let go of the tiller and relit his pipe, while the yacht rounded sharply to, and in a twinkling was tossing head to sea with loud claps of her canvas and passionate jerks of her boom, as the wind leapt on its quarry, now turning to bay, with redoubled force. The sting of spray in my eyes and the Babel of noise dazed me; but Davies, with a pull on the fore-sheet, soothed the tormented little ship, and left her coolly sparring with the waves while he shortened sail and puffed his pipe. An hour later the narrow vista of Als Sound was visible, with quiet old Sonderburg sunning itself on the island shore, and the Dybbol heights towering above—the Dybbol of bloody memory; scene of the last desperate stand of the Danes in ’64, ere the Prussians wrested the two fair provinces from them.

‘It’s early to anchor, and I hate towns,’ said Davies, as one section of a lumbering pontoon bridge opened to give us passage. But I was firm on the need for a walk, and got my way on condition that I bought stores as well, and returned in time to admit of further advance to a ‘quiet anchorage’. Never did I step on the solid earth with stranger feelings, partly due to relief from confinement, partly to that sense of independence in travelling, which, for those who go down to the sea in small ships, can make the foulest coal-port in Northumbria seem attractive. And here I had fascinating Sonderburg, with its broad-eaved houses of carved woodwork, each fresh with cleansing, yet reverend with age; its fair-haired Viking-like men, and rosy, plain-faced women, with their bullet foreheads and large mouths; Sonderburg still Danish to the core under its Teuton veneer. Crossing the bridge I climbed the Dybbol—dotted with memorials of that heroic defence—and thence could see the wee form and gossamer rigging of the Dulcibella on the silver ribbon of the Sound, and was reminded by the sight that there were stores to be bought. So I hurried down again to the old quarter and bargained over eggs and bread with a dear old lady, pink as a débutante, made a patriotic pretence of not understanding German, and called in her strapping son, whose few words of English, being chiefly nautical slang picked up on a British trawler, were peculiarly useless for the purpose. Davies had tea ready when I came aboard again, and, drinking it on deck, we proceeded up the sheltered Sound, which, in spite of its imposing name, was no bigger than an inland river, only the hosts of rainbow jelly-fish reminding us that we were threading a highway of ocean. There is no rise and fall of tide in these regions to disfigure the shore with mud. Here was a shelving gravel bank; there a bed of whispering rushes; there again young birch trees growing to the very brink, each wearing a stocking of bright moss and setting its foot firmly in among golden leaves and scarlet fungus.

Davies was preoccupied, but he lighted up when I talked of the Danish war. ‘Germany’s a thundering great nation,’ he said; ‘I wonder if we shall ever fight her.’ A little incident that happened after we anchored deepened the impression left by this conversation. We crept at dusk into a shaded back-water, where our keel almost touched the gravel bed. Opposite us on the Alsen shore there showed, clean-cut against the sky, the spire of a little monument rising from a leafy hollow.